That depends instead on the strength of links from one area to another-places that have lots of social ties are likely to receive information more quickly than those that have weak ties.Īnd indeed, that’s exactly what Kallus and co find.

That’s because geographic distance is not the key factor in the spread of information over social networks. Indeed, the spread of the video when plotted against geographic distance from South Korea looks more or less random. It also has stronger English language links.īut none of that reveals the classic wavelike pattern that epidemiologists expect when viral events occur.

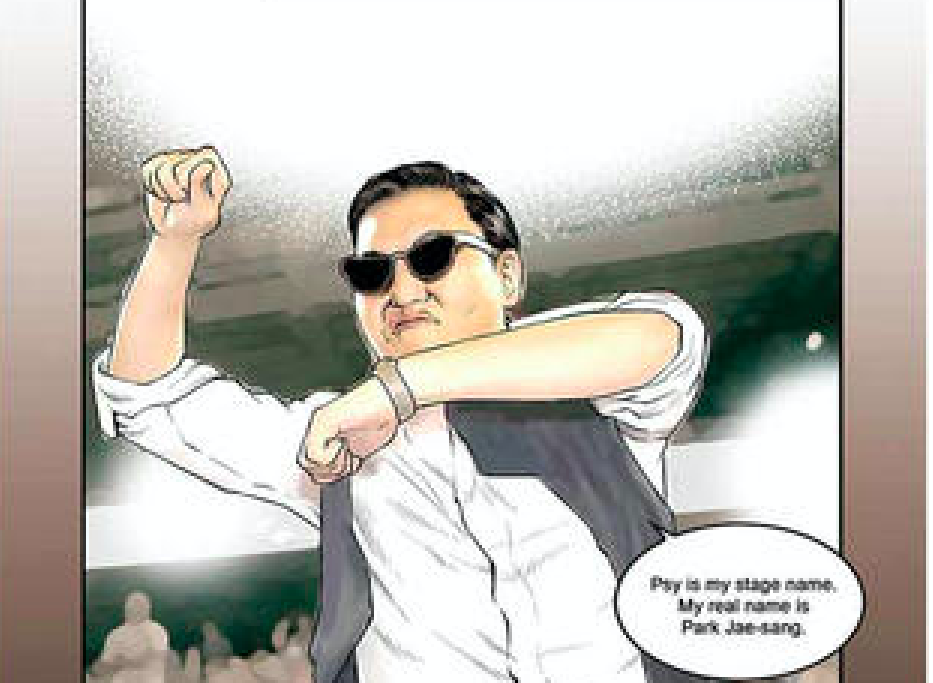

That’s probably because the Philippines is relatively close to South Korea but has stronger links to the rest of the world through its diaspora. That reveals the way the video spread, initially to the Philippines and from there to the rest of the world. To do this, they tracked the spread of the video by searching the historical Twitter stream for geolocated tweets that mention “Gangnam Style.” “Location information allows us to record the approximate arrival time of a certain news to a specific geo-political region,” say Kallus and co. Just how this happened is the focus of Kallus and co’s work. “In 2012, the record breaking ‘Gangnam Style’ marked the appearance of a new type of online meme, reaching unprecedented level of fame despite its originally small local audience,” say Kallus and co. By December 21, 2012, however, the video had become the most viewed in history when it reached a billion views of YouTube across the globe. It was released on July 15, 2012, and immediately become popular in South Korea.īut since Psy was unknown outside the country, the video’s later success was hard to predict. This music video was produced in a style known as k-pop by a South Korean musician called Psy, who was relatively unknown outside his home country. The story behind this video pandemic is extraordinary. And the team say it is possible to recover the unique wavelike signature of information spreading, providing they properly take account of the social networks involved. Today, Zsofia Kallus and pals at Eotvos University in Budapest, Hungary, say they have found just such an example in the way that Psy’s Gangnam Style video spread across the globe in 2012, eventually becoming the first to receive over a billion views on YouTube. To solve this conundrum, network scientists would dearly love to have an emblematic example of the way a specific piece of information has spread across the globe in a measurable way. And that raises the question of whether it is really wavelike or fundamentally different. And because this happens from person to person through a social network, it should follow a wavelike spreading pattern.īut observing this pattern is hard because the geographical spread of information is distorted by the social media networks along which it moves. Social phenomenon, such as songs, tweets, videos, and so on, are thought to spread in a similar way. By normalizing the spread in this way, a wavelike spreading pattern reemerges. However, network theorists found they could restore the wavelike nature of the spread if they account for the speed of travel. Air travel suddenly allowed diseases to jump from one continent to another at breakneck speed. This spread of this particularly virulent form of bubonic plague that killed between 35 and 200 million in the 14th century was limited by the transport that was then available.īut something strange happened in the 20th century, when that wavelike form of spreading seemingly vanished. Historical records show that the Black Death traveled across Europe at about two kilometers a day. The speed of this wave is governed by the methods of travel. The outbreak begins at a specific place and time and then spreads in a wavelike pattern away from the source. The spread of disease has always followed a clear pattern.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)